NB: I’m aware of Coros's recent focuses on tracking and improving climbing, but haven’t had the opportunity to try it.

When I visit the climbing hall, I rarely see people logging data about their climbs. People are often sporting Garmins or Apple Watches, but not using them there. As a datavore, I find this interesting.

I track climbing, because I track everything. At a basic level, I’m interested to see heart rate when I fall off (did I fall due to technique, or exhaustion?), and logging grades (I find, perhaps due to my dyslexia, remembering climbing grades to be about as fun as counting lengths in a pool, which is to say I’m bad at it and this frustrates me). Deeper into the data gathering realm, I’ve tried to quantify ‘pump’, or more interestingly, when pump has subsided and the optimal time to resume climbing after a fall has arrived.

I’m also interested how the sports quantification community as a whole understands climbing. Whoop, Garmin, and Strava, for example: do they treat it the same as just HR, or, has the science advanced enough to allow for accurate effort quantification and recovery estimation, as it has for running and cycling? (Spoiler, like swimming, it’s poorly represented).

Did I fall off due to technique or exhaustion?

Fundamentally, one problem knows the answer to this, but after observing my HR data during climbing, I can sustain ascent until about 170bpm, and after that I’d better be near to the top. Watching pro-climbers on YouTube, I’m see HRs climb to 185, which gives me a scale: I can run and cycle at that range, but not climb. So, if I fall off at 145bpm, I should probably check my technique (fuck off, beta, that word is irksome) and try again. Falling off at 165? Time for a rest, maybe come back tomorrow. If I’m falling off at 185bpm, I could start looking for sponsors…

Bro, how pumped am I?

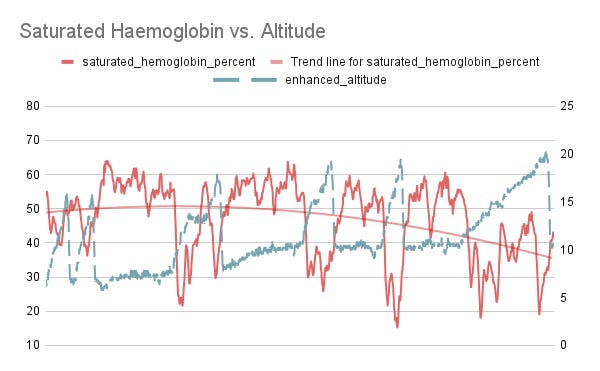

I haven’t seen research into the quantification of pump, or the state at which one’s forearms resemble Popeye’s, and one can no longer hold on. I conducted my own research by wearing a muscle oxygenation sensor (an old Humon Hex) on my forearm, and observing the ebb and flow of oxygen saturation levels compared to climb point and HR. I noticed the following (to no climber’s surprise):

1. The first few climbs show poor tissue saturation. This is to be expected, as my muscles have yet to warm up: the blood vessels are still in their rest state, supporting normal efforts.

2. After about 3 ascents, peak saturation is reached. Time to work on hard problems.

3. Around climb 6 and onwards, tissue saturation recovery rates decrease: I need more reset between each climb, and the recovery isn’t quite as much.

4. By ascent 10, we are deep into diminishing returns.

5. The most valuable datum: when I fall off due to exhaustion, the optimum HR to resume climbing at is 135bpm. Prior to this, I was resuming climbing when my HR dropped to 145bpm, but by waiting until 135bpm, I find my subsequent attempts are more successful, and less strenuous.

Let’s integrate that last point again:

when I fall off due to exhaustion, I should hang on the rope until my HR is at 135bpm or below before I resume climbing

Given that I only climb (not boulder) once a week, this one datum has massively improved my climbing experience, and allowed me to progress faster than previously.